For the video of the activity, please click the link below:

http://heritap.whitr-ap.org/index.php?classid=12497&id=54&t=show -P2

Traditional Knowledge Systems are reflected in the indicators of the quality of life connecting to the four dimensions of sustainable development. Communities have played a key role in traditional knowledge systems of the World Heritage site, therefore their values should be recognized, respected and understood, which will contribute to sustainable urban and rural development through heritage conservation and management. The traditional knowledge systems are dynamic, continuously optimized and have endured the testing of time. They link to every aspect of community life, such as enhancing community resilience, improving quality of life, and realizing the positive interaction with urban and rural sustainable development.

Group Photo © ZHANG Hanqi

1.Traditional Knowledge Systems are reflected in the indicators of the quality of life connecting to the four dimensions of sustainable development.

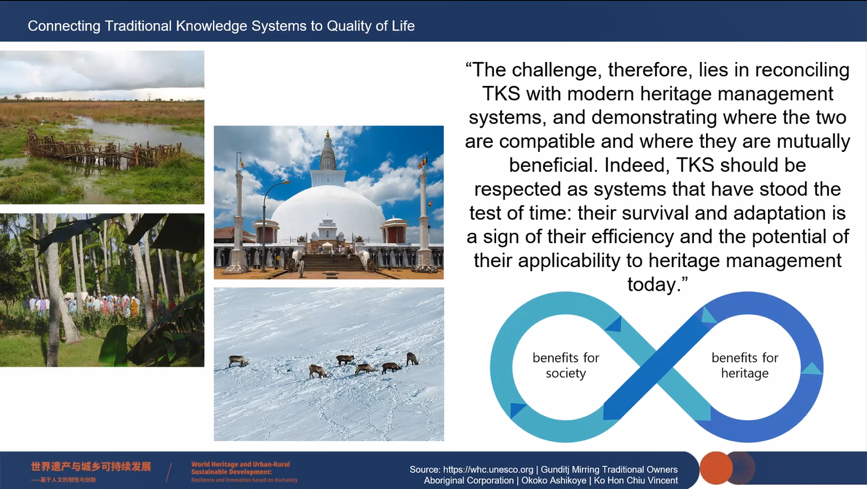

Gamini WIJESURIYA, special advisor to WHITRAP Shanghai, and Sarah Court, expert member of ICOMOS scientific committees, introduced the definition of ‘Quality of Life’ and ‘Traditional Knowledge Systems’, and how Traditional Knowledge Systems connect to the quality of life of communities and how this can be supported in heritage places. By the time of the adoption of the World Heritage sustainable development policy in 2015, quality of life and well-being were seen to be connected to each of the sustainable development dimensions (namely inclusive social development; inclusive economic development; environmental sustainability; and peace and security). If these dimensions are achieved at World Heritage properties, they can contribute to both heritage conservation and the quality of life of local communities and communities in general. In this context Traditional Knowledge Systems have become an important area for consideration. It focuses on how different indicators of the quality of life can be connected to the four dimensions of sustainable development, and shows how these are embedded in Traditional Knowledge Systems. In light of this understanding, heritage becomes an important context in which Traditional Knowledge Systems can be supported so that communities continue to benefit from them and recognize that Traditional Knowledge Systems can play an important role in the conservation of heritage. As the World Heritage Convention reaches its 50th anniversary and it places more emphasis on connecting heritage to sustainable development efforts, this nexus between Traditional Knowledge Systems and quality of life seems a promising area for future efforts.

Connecting Traditional Knowledge Systems to Quality of Life © Gamini Wijesuriya and Sarah Court

2.Communities have played a key role in traditional knowledge systems of the World Heritage site, therefore their values should be recognized, respected and understood, which will contribute to sustainable urban and rural development through heritage conservation and management.

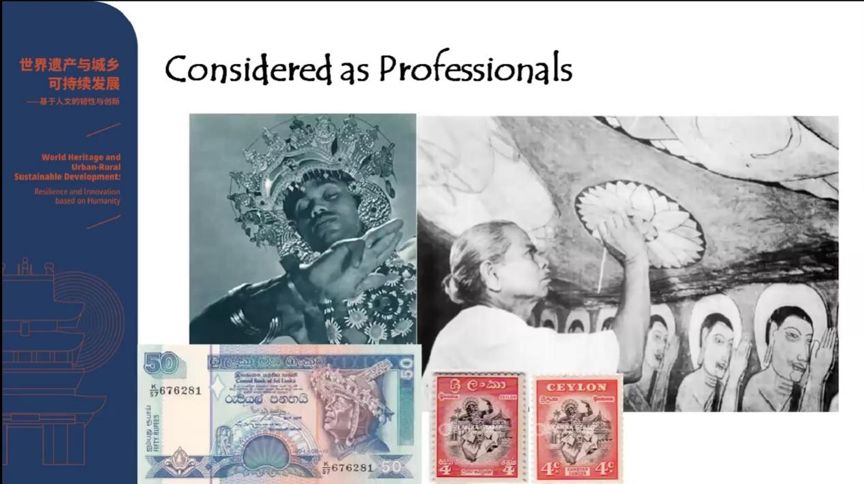

Artists and craftsmen in the sacred tooth relic temple © Prasanna B. RATNAYAKE

Prasanna B. RATNAYAKE, Department of Archaeology of Sri Lanka, showed us the virtuous circle of community life formed by heritage. The sacred tooth relic of Buddha, kept in the sacred tooth relic temple in Kandy, was listed as a World Heritage site in 1988. Through the period of nearly two millenniums, the traditional system to protect and worship the tooth relic has continued to date, together with those socio cultural and religious traditions supported by different artists and craftsmen. The annual perahera was one of the most notable events of the traditions where they perform their best skills. Thus, they could seek several sources of revenues and have access to higher levels of livelihood in the society. In addition, their moral life had also enhanced and therefore led to a better ethical standard. Most of them had been popular by name and considered as professional artists now. Therefore, they tended to continue their traditional skills together with their own next generation and transfer those skills to the others who are interested.

France Poulain, a State Architect and Town Planner of France, was concerned about a growing gap between people who seek and promote ancient traditional techniques and those who were ready to destroy our heritage to rebuild the city of tomorrow. According to conclusions of studies and researches, a more desirable way to treat old buildings were to expose and retain the qualities of status quo, but manufacturers on the contrary wanted to sell their unsuitable building improvement techniques at all costs. For example, old buildings undergoing thermal insulation from the outside will loss both their architectural qualities and performance qualities. This had already been seen in Germany for several years and it is spreading in France. So, Poulain appealed to local associations to be decisive in the choice and methods of restoration for larger spaces. Meanwhile, they were waiting to see if the old management methods could survive and preserve these hundreds-of-years-old buildings.

Rubremont Church, France © France POULAIN

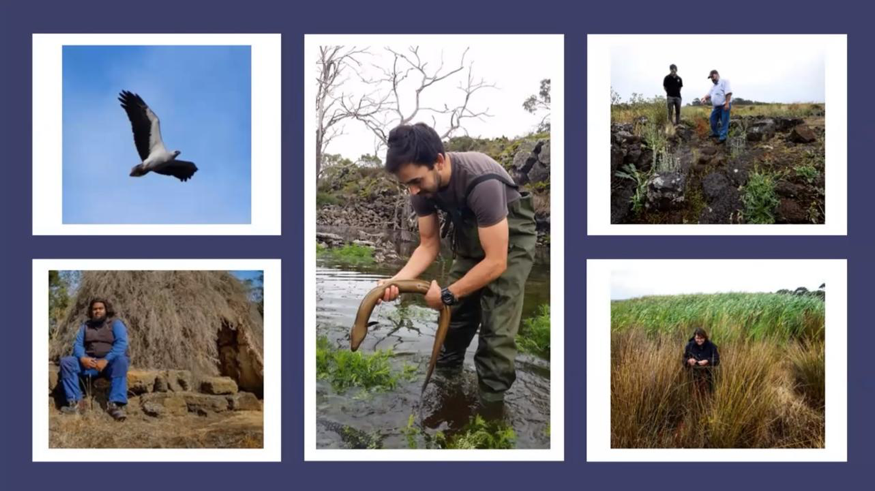

Indigenous Protected Areas and a National Park © Erin Rose

Erin Rose, a World Heritage Senior Advisor, introduced the natural management method of Budj Bim Cultural Landscape. The volcanic landscape there was altered to create the world’s oldest aquaculture system, dating to at least 6,600 years old. The Budj Bim Cultural Landscape was a living entity that has catered to Gunditjmara for thousands of years. It was made up of 3 serial components and was protected for its cultural and natural values – Indigenous Protected Areas and a National Park. Australia ensured ecological improvement through natural resource management and cultural heritage protection including cultural burning, cultural heritage management, research projects, revegetation, cultural water flows and wetland and riparian restoration works. A customary management approach was used to protect the landscape, keeping the resources and cultures for generations.

Åsa Nordin Jonsson, Site Manager of World Heritage of Laponia in Sweden, shared the case of Sami traditional knowledge and the management of the world heritage Laponia. Sami traditional knowledge is passed on from generation to generation, and should have a central role in the management of the world heritage. However, there are no instructions on how to integrate traditional knowledge in the management, so they decide to seek support from the Sami people who have knowledge and experience through traditional board meeting to bring different people together and discuss how to conduct the management with different situations. For example, to construct buildings in heritage sites while considering the natural habitats for local creatures, we should combine different methods in the management to preserve the world heritage for future generations and get Sami people involved as well. As for the acceptance of different norms and values of local communities, we should find our own way to learn about the traditional knowledge and embrace the cooperative attitude.

Board meeting with Sami people © Åsa Nordin Jonsson

3.The traditional knowledge systems are dynamic, continuously optimized and have endured the testing of time. They link to every aspect of community life, such as enhancing community resilience, improving quality of life, and realizing the positive interaction with urban and rural sustainable development.

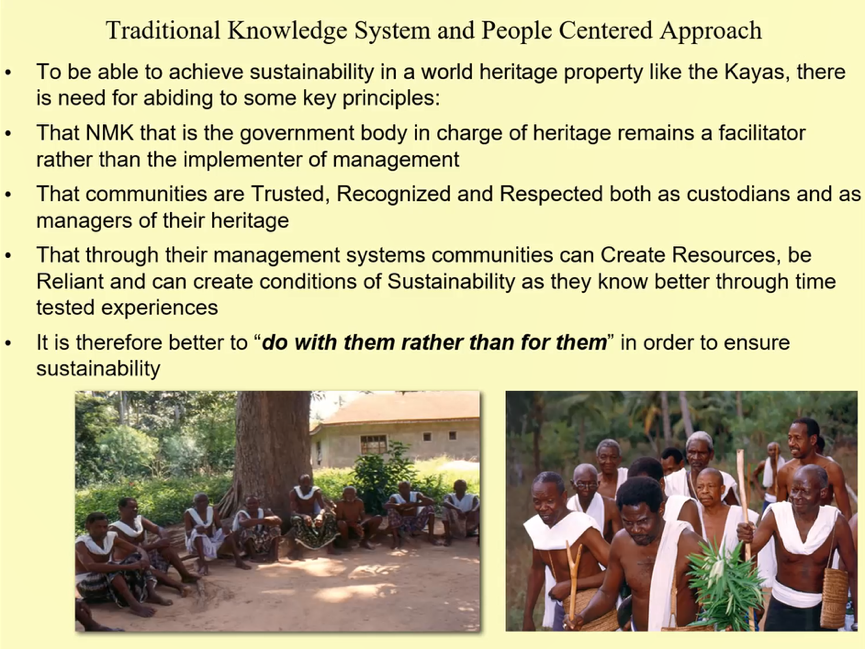

George Okello ABUNGU, Emeritus Director-General of the National Museums of Kenya, provided a case of sustainable lifeway through traditional knowledge systems and a people centered approach in Kaya Forest and the Mijikenda community. He introduced that the Kayas are living forested settlements rich in biodiversity, spiritual and religious significance where important elders of the communities are buried and play a central and important role in the lives of the communities. The Kayas are listed as a World Heritage site under the UNESCO 1972 Convention and as heritage of humanity under the 2003 Convention, which have contributed to cultural, social and economic wellbeing of the Mijikenda community. Due to their biodiversity, they are also abundant in various resources of medicinal plants. As sacred sites they play a major role in the spiritual well-being of the community bonding them together as people with common goals and common benefits. Managed fully by the elders, the Kayas have also become an attraction to visitors where other relevant activities are hosted. The community also attracted the political attention related to national policies and budget, thus fostering economic sustainability in local community. He suggested that communities should be trusted, recognized and respected, so it is better to work with communities rather than work for them in order to ensure sustainability.

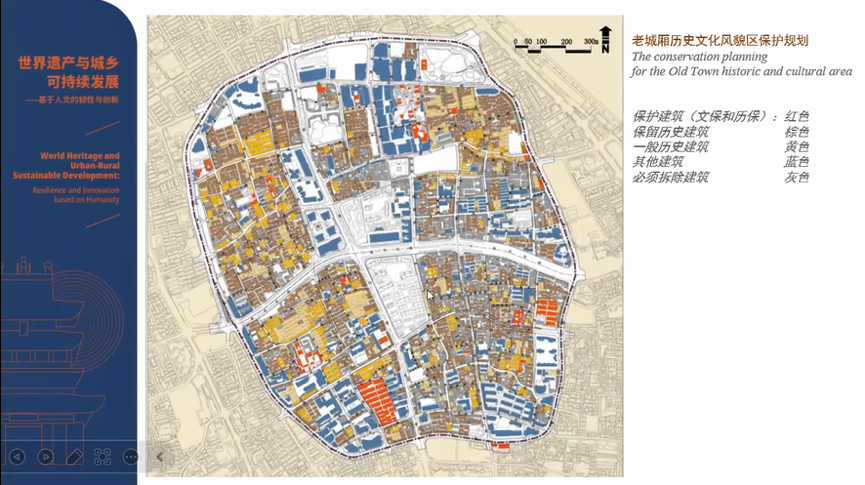

The conservation planning for the Old Town historic and cultural area © Zhang Song